RANKING THE JAMES BOND MOVIES

25) Quantum of Solace (2008)

It’s interesting to ruminate on the fact that when I first saw this in theatres, it was nowhere near the bottom of my list but with each and every subsequent viewing my opinions and outlook on this film get worse and worse to the point where I find it just unwatchable. The score by David Arnold is great and – unlike another Craig movie we’ll get to very, very soon – there are some decent action scenes but these cannot salvage a film that’s kneecapped by choppy editing and asinine and highfalutin attempts to be something more than good thrillers.

24) Die Another Day (2002)

Yeah, does anyone like this? Die Another Day is one of those movies which I’ve seen more times than I care to admit, and yet, regardless of how often I watch it in its entirety, it never fails to astonish me just how poor this film is. For the longest time I always looked back on Die Another Day as being the James Bond equivalent of, say, Batman and Robin (1997): an enjoyably bad romp that you could knowingly laugh along with. The harsh and plain reality is that that’s not the case – it’s just, well… bad. Admittedly it starts off pretty well, the David Arnold score is reliably satisfactory and the car chase between the Aston and the Jag is entertaining, but a good soundtrack and the odd moment of excitement aren’t strong enough to redeem this mess. Everything takes a swift nosedive as soon as Halle Berry shows up and the action moves to Iceland.

23) SPECTRE (2015)

My thoughts on this closely echo those of Quantum of Solace; as I walked out of the cinema upon seeing SPECTRE, my immediate reaction was admittedly lukewarm but overall one glowing with positivity. However, much like QoS, the more I watch it and the more I think about it, I again come to the damning verdict that this is just an unpleasant watch, Bond-fan or not. I honestly struggle to comprehend how anyone can say they enjoy this. At its best it is bland; at its worst it is numbingly stupid. The most heinous crime it commits is, of course, its bungled execution of Blofeld, Bond’s iconic arch-nemesis whose absence in the official series dates back to 1971 (minus a questionable cameo in the opening of FYEO), but even beyond that this movie didn’t even have the dignity to provide us with any blood-pumping set-pieces that folks will remember for years to come. Additionally, the contrived and laboured attempt to convince us that Madeleine Swann is somehow the love of Bond’s life also falls flat. Hell, even the pre-title sequence in Mexico that everyone fawned over simply isn’t as impressive as the ones seen elsewhere – I.E. GoldenEye. The one saving grace of this picture is the train fight between Bond and Hinx, but even that doesn’t compare to the one in FRWL.

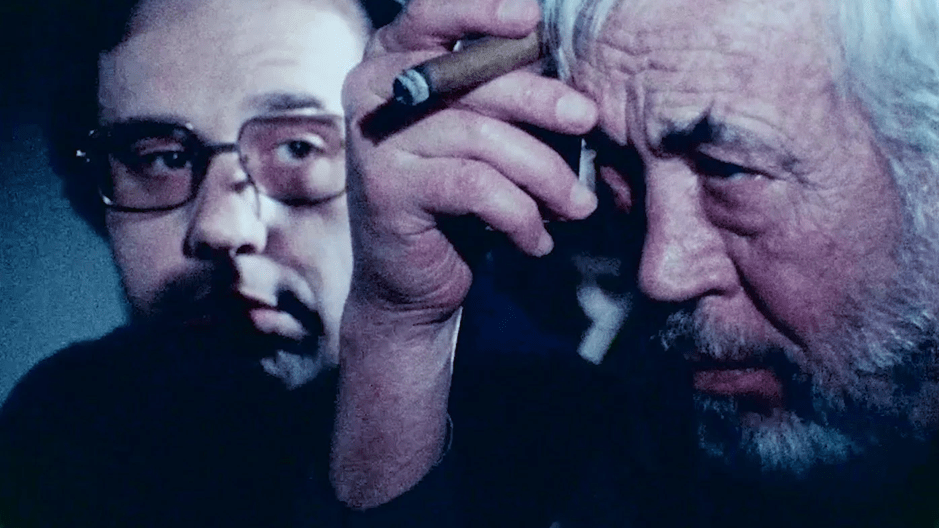

22) Diamonds Are Forever (1971)

Those who lambast the Moore era for being camp and kitsch either A) haven’t seen DAF, or B) conveniently choose to overlook the fact that the camp and kitsch factor began here. There’s a real sense of trashy sleaze here that is seldom seen elsewhere in the rest of the series. At least Sean Connery – a noticeably atrophied and haggard looking Connery, at that – looks like he’s having fun (no doubt the $1.2 million cheque had something to do with that).

21) A View to a Kill (1985)

Effortlessly charming and affable as he may be, the fact that Roger Moore was able to continue to play 007 well into his late fifties continues to be a bothersome source of bafflement to me and nowhere is that icky and unshakable pain felt more prominently than it is here in what would be his belated swansong. There’s a lot that can be said of AVTAK but it all traces back to Mr. Moore who, at fifty-seven years old, is no longer a convincing man of action; the idea of twenty-something miss universes fawning over him is ludicrous, as is the prospect of him somehow being unbeatable in a fistfight. The whole film just feels odd (and not in a pleasant way), as the dynamic of pitting the young and the quirky – Grace Jones – against the incongruously doddery Moore just feels wheezy and jarring.

20) The Man with the Golden Gun (1974)

TMWTGG is a harmless but inconsequential Bond outing that ticks all the boxes of what constitutes a Bond movie, but it’s also (dare I say) quite a bore. The only thing that elevates this above the likes of Diamonds and View is the presence of the ever-wonderful Christopher Lee as the titular assassin-for-hire. Oh, and the less said about that awful whistle noise during that brilliant car stunt, the better.

19) Tomorrow Never Dies (1997)

If you were to put all the data into a machine (sort of that like that computer from Willy Wonka) and ask it to produce a Bond movie, the result would most likely be Tomorrow Never Dies. On the surface it has everything that makes a Bond film enjoyable but, consequently, it’s also one of the most generic.

18) The World is Not Enough (1999)

I actually think this film gets a bad wrap and, frankly, I’m not entirely sure why. Yes, Christmas Jones is a stupid character, but there are elements in this film that were quite forward-thinking at the time: M being an integral catalyst in the plot; a female villain; a chase through London. Good stuff.

17) Thunderball (1965)

Growing up a Bond aficionado in the pre-Craig era, one couldn’t pick up a magazine or browse the fansites and forums without seeing a mention of two movies that were held up high as being the Bond movies to beat: Goldfinger and Thunderball. While I agree that the former is and perhaps always will be the “gold standard” (pun intended) of all future Bond adventures to come, I must confess that the appeal of the latter has always remained a mystery to me. Yes, in a pictorial sense, this is a handsome movie in terms of its pictorial quality – the eye-popping colours, the exoticism of the locations and the silky soundtrack – but superficial stuff aside, I’ve always found Thunderball to be a bloated and boring blockbuster. I’ve heard and read many outlets lucidly convey why this movie is as beloved as it is, but as far as I’m concerned they may as well be telling me that grass is purple, because I just don’t see what they see. I genuinely feel guilty for ranking this outside the top ten, but honesty demands that I proclaim that Thunderball is the most overrated Bond movie made.

16) Octopussy (1983)

Now we go from a Bond movie I’ve never cared for to one that I’ve always harboured something of a soft spot for. Of all the films in the franchise, this is probably the one I’ve seen the most, thanks large part to fact that I find it the easiest and most agreeable to watch. It’s a proper Boys Own adventure and the Indian setting is a real beauty for the eyes.

15) Moonraker (1979)

I have little doubt that the fact that I have placed Octopussy and Moonraker (I.E. that one where Bond goes to space) higher than Thunderball will arouse plenty of ire from the fans, but the fact of the matter is that I’ve always liked Moonraker and never found it as preposterous as others would have you believe. Yes, yes, of all the Bond movies this is probably the most excessive and the egregious, but in terms of style and spectacle very few films compare.

14) The Living Daylights (1987)

After a dozen years of Moore shenanigans, The Living Daylights takes us back to Bond’s roots – a Cold War thriller where Bond himself is a blunt instrument. The title song by A-Ha is one of the very best, Dalton’s brilliant (don’t let anyone tell you otherwise) and the location work is spectacular. The only downside is the lack of a compelling or colourful villain.

13) For Your Eyes Only (1981)

This is one of those Bond adventures that has improved with age. After the madcap spectacle of Spy and Moonraker, seeing our hero involved in a good old fashioned slice of Cold War espionage may have been quite a comedown, but that added grittiness makes for one of Moore’s best.

12) Licence to Kill (1989)

I don’t think there’s ever been a Bond movie wherein my opinion of it has shifted so drastically over time like it has with Licence to Kill, Dalton’s second and (regrettably) last outing. It many ways, it’s the opposite of SPECTRE; growing up as a fan devouring all the movies, LTK was the one Bond adventure that I truly loathed and went out of my way to avoid. Today, however, my mind boggles to think how anyone could dislike it and I now laud it for all the reasons I previously detested it. Granted, while I wouldn’t label it a “cheap” film as some have, it is undeniably a very dry looking film, lacking any of the visual verve and dynamism of the previous epics and it does stray perhaps a tad too far from the formula – often times resembling a concoction of Miami Vice, Brian de Palma’s Scarface and Man on Fire – and it is dark, and violent and almost totally devoid of humour. But that’s what makes it so interesting. Best of all, though, is the man playing 007 himself. While he may lack the magnetic star power and cinematic presence of Connery and Moore, Dalton quite simply is Ian Fleming’s creation made flesh and blood and the fact that he was denied a third and possibly a fourth chance to bring his unique interpretation to the silver screen remains a crying shame.

11) You Only Live Twice (1967)

Lewis Gilbert as director. Ken Adam once again the set designer. Japan as the setting. Donald Pleasance as Blofeld. YOLT has all the makings of a classic. It’s a shame (and slightly ironic), therefore, that the only weak link in the chain is Bond himself. Just as Christopher Lee was becoming rapidly disenchanted playing Dracula for Hammer, a visibly despondent Sean Connery was reaching the nadir of his interest playing the role that made him a global superstar. Had Connery brought his A-game, this would have easily been top-tier Bond material but, as it stands, it’ll have to settle for the tenth spot.

10) No Time to Die (2021)

It may be a bit presumptuous to place the latest Bond outing in the top ten. It isn’t a perfect Bond movie, and it’s sure to divide the fandom for years to come – but as a conclusion to the epoch of Craig, NTTD is a soundly directed, acted and gorgeous feast for the senses.

9) Live and Let Die (1973)

A solid debut for Moore. Boat chases through the bayous. A colourful array of villains. Paul McCartney’s title song.

8) Dr. No (1962)

It’s quite surreal watching Dr. No, much in the same way it’s strange to watch William Hartnell playing the Doctor; the novelty is obvious: it’s the first movie, so it holds some prestige before you even sit down to watch it in its entirety. Lamentably, when compared to its successors, it’s easy to see why some viewers may find the first Bond outing to be a tad vanilla. When contextualised and seen in isolation, however, what we have is grand, old-fashioned and immensely pulpy British thriller with a distinct (albeit modest) flavour of exoticism and eroticism. The plot is your standard Sax Rohmer affair and it’s directed in a fairly workmanlike sort of way by Terence Young, but the natural screen charisma of its leading star, the instant sex appeal of its heroine and the beauty of its Caribbean setting all come together wonderfully to make Dr. No the perfect first chapter in cinema’s greatest franchise.

7) GoldenEye (1995)

Looking back, it’s a real shame how Pierce Brosnan’s tenure as Bond worked out. Having been left standing at the alter twice before, the fifth man to don the tux finally got his chance in 1995, but a lot was riding on his shoulders. Following a six year hiatus, a lot had changed since Bond was last on the screen and many pundits pondered on whether the world actually needed an archaic figure like 007 anymore – and yet, when GoldenEye hit cinemas, the answer proved to be a simple but resounding “YES”. While his remaining three films shifted from being forgettable to downright terrible, Brosnan can rest easy knowing that he and the rest of the team gave us a truly great Bond movie in GoldenEye. The game was pretty great, too.

6) The Spy Who Loved Me (1977)

The movie that, like GoldenEye, saved the franchise and proved that nobody does it better.

5) Goldfinger (1964)

Had this ranking been done ten, twenty years ago, chances are that this film would have topped the list. The passage of time and the Craig films has made the flaws more noticeable, but Goldfinger remains the gold-standard (pun intended) for the franchise.

4) Casino Royale (2006)

A film that gets better the more I watch it. The perfect Bond movie for the post 9/11, post Bourne age.

3) From Russia With Love (1963)

The first Bond I ever saw. Such a status perhaps implies an inherent bias, but even with that removed, this is still a damn great thriller of the classic mould.

2) Skyfall (2012)

It’s beyond baffling to think that Craig has had such a yo-yo, almost bipolar tenure as Bond; as of today, he’s donned the tux four times – two of which rank as the very worst and two which rank as the very best (the logical pattern therefore dictates that No Time To Die should be amazing). Anyway, while it seems that it’s become fashionable to bash Skyfall, the most financially successful movie to date,

1) On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969)

For the longest time, OHMSS was something of a forgotten underdog within the Bond canon, a cultish curio that only the infuriating hipsters would speak up about and fawn over. Now, however, this much-maligned film is finally getting the recognition it deserves. Everything here is brilliant (well, almost everything): Diana Rigg, Peter Hunt’s polished direction, the superb cinematography and, of course, the best script any Bond movie has ever had. The only downside? The Aussie fella playing Bond.