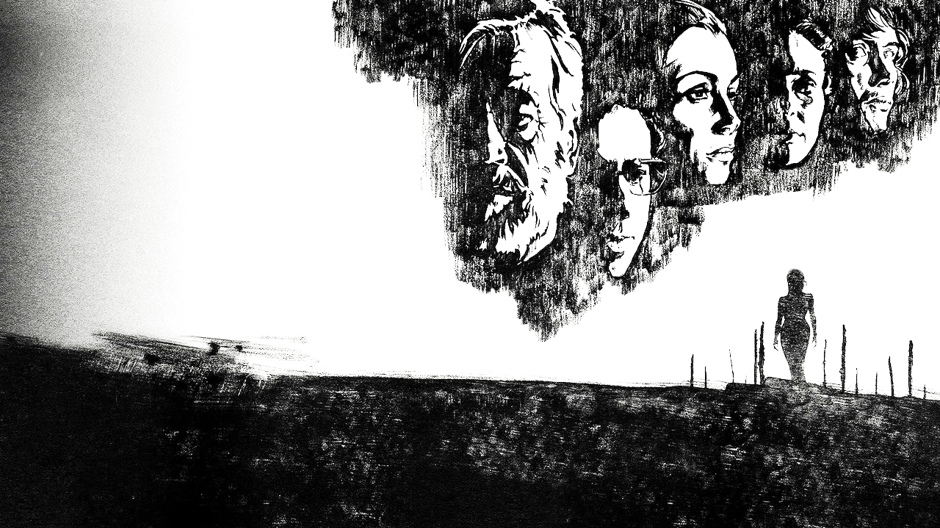

THE OTHER SIDE OF THE WIND (2018)

“Movies and friendship. Those are mysteries.”

As you are no doubt aware, I’m a voracious consumer of all things film related. From an early age I was corrupted by the mesmerising magic of it all, and various names corrupted me. John Ford corrupted me, as did Hitchcock and Hawks, but it is Welles, the man who scared the wits out of an entire nation with his radio broadcast of The War of the Worlds (1938) and the man who made the greatest picture ever made, who enraptures me the most. Thirty-five years after his passing, he continues to leave a lasting impression through the immortal words and works that he left behind. Today’s review is a humble tribute to that man among men.

I’ve often said that the best films are the ones that were never made or are destined to never see the light of day, and the history of film is littered with them. There was Alexander Korda’s ambitious but ill-fated attempt to adapt I, Claudius in 1937; Charlie Chaplin and Stanley Kubrick both wanted to make a feature film about Napoleon Bonaparte, respectively, but were equally unsuccessful; Alejandro Jodorowsky’s Dune remains a potent source of fascination; and Terry Gilliam’s much publicised attempt to bring Don Quixote to life is legendary.

The greatest victim of this epidemic, however, was Orson Welles, the cinema’s polymath and Hollywood’s one-time wonder boy who gave us a wealthy treasure chest of lauded masterpieces like Citizen Kane (1941), The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) and Touch of Evil (1958) to name just a few – but there could have been so many more. Throughout this towering titan of a man’s tragic career, which began with a glittering high only to quickly dissipate into wine commercials and a tidal wave of chat-show appearances by the end of his life, he endeavoured many projects that would never come to fruition, including Don Quixote, Joseph Conrad’s novella Heart of Darkness – which would later come to the screen in the form of Francis Ford Coppola’s Vietnam War epic Apocalypse Now (1979) – and The Merchant of Venice. The sheer breadth of these titles reveal the scope of Welles’ artistic ambition. There was also another project: The Other Side of the Wind, which began life as an experimental comeback for Welles’ whose career had sagged to the point of exile in Europe where he made a number of adventurous but little-seen pictures like The Trial (1962) and Chimes of Midnight (1965), but persistent problems and Welles’ untimely death put an end to that. Or so we assumed.

Nearly five decades has passed since principal photography commenced, and Welles’ picture has finally been fully edited and entered circulation. So, was it worth the wait? In a word: yes. Despite reservations and anxieties, this long-lost chapter in what is already an impressive filmography surpasses even my expectations.

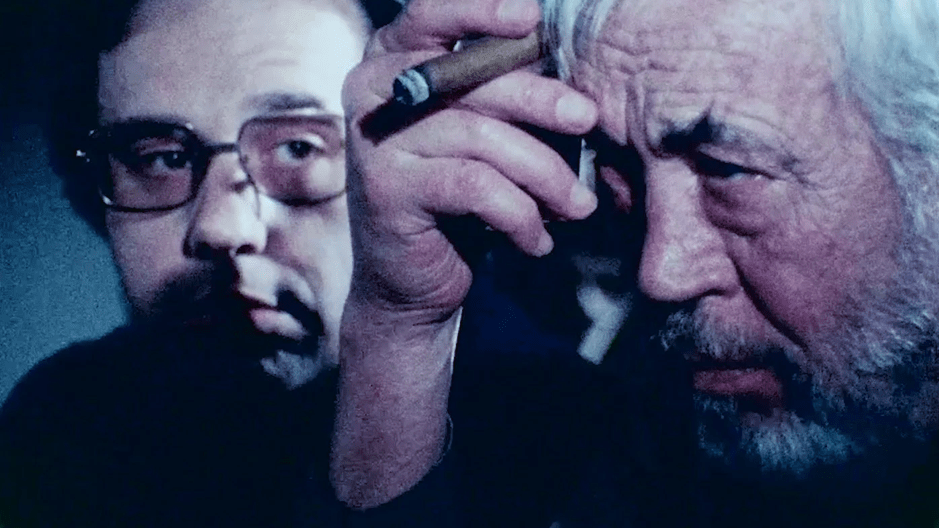

Hollywood, more so than us Brits, has a neat track record of making movies about movies – some of these possess the sentimental, fairytale quality like Singin’ in the Rain (1952) and Ed Wood (1994), while others seek to unveil the darker side of the dream factory such as Sunset Boulevard (1950) or Living in Oblivion (1995). The Other Side of the Wind is another such example of a film about films and those colourful, slightly crazy individuals that make them, but with that distinctive Wellesian flair. Presented in an unconventional cinéma vérité style, featuring rapid cutting and a combination of colour and black-and-white footage, it concerns an ageing legend in the directing business, played by John Huston, who fell out of favour with Hollywood but returns to host a screening party for his latest (and, ironically, unfinished) project.

An exploration of desperate desire and an elaborate polemic on the state of the film establishment (the decline of the old Hollywood studio system and the emergence of the new dominant breed of filmmakers inspired by the atmospheric, avant-garde cinema from Europe like Bergman, Antonioni and Demy), this encapsulates, in excitingly electrifying fashion, the anguishes and agony that come hand-in-hand with the process of making a film. There’s a genuine aura of spontaneity to the picture; it has the chaotic, disorderly, untidy attitude of a collapsing circus inhabited by these scattered souls, all of whom are fascinating figures – none more so than the character of the director. Despite his claims to the contrary, the director, a macho maverick and intellectual darling who feels like an amalgamation of Rex Ingram and Ernest Hemingway, is clearly a thinly-veiled reflection of Welles himself. The rest of the clan of characters also represent members of the film community of the time, including critic Pauline Kael and screenwriter John Milius. As the film-within-a-film’s leading lady, Oja Kodar, Welles’ co-writer and muse, is utterly magnetic – armed with a marvellously vulpine, almost satanic, face that is equal parts pulchritudinous and inscrutable, the exotically erotic Kodar oozes an almost dreamlike sensual nature that is most uncommon in Welles’ notably prudish work.

The Other Side of the Wind is a tragic tale about greatness and how fragile it can be. It isn’t Orson’s best (as the saying goes: “it ain’t no Citizen Kane“), but it is his most profound and personal, and it is a testimony to his complex, cathartic creativity – for that I can find no reason not to recommend it to any film freak or fan. The companion documentary, They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead is worth a watch, too.